Wednesday, February 5, marked what would have been the 100th birthday of one of the 20th century’s most important and notorious writers: William S. Burroughs.

Burroughs was one of the original Beat poets, and helped spark a cultural revolution. He wrote like no one had before, about topics considered impolite, if not obscene, at the time.

Burroughs was openly gay, and wrestled with heroin addiction much of his life. He lived, famously, in New York, Paris, Mexico City and Tangiers, but he spent the last years of his life in Kansas. In fact, Burroughs lived longer in Lawrence, Kan., than anywhere else.

That may seem a strange fit for the groundbreaking author of Naked Lunch, Queer and Junky, but Burroughs and Lawrence formed a warm and enduring relationship.

Lawrence still has a personal connection to Burroughs

In Lawrence, Kan., you can still get a haircut from William Burroughs’ barber. Marty Olsen runs Do’s Deluxe, a few blocks east of the main drag.

“I cut William’s hair for 13 years,” remembers Olsen. “I cooked dinner for him a few times and went to a few parties over at his house.”

Burroughs moved to Lawrence in 1981.

“He needed to get out of New York,” says Olsen. “There was some backsliding going on in his world there.”

Burroughs had been living in a very gritty part of lower Manhattan. A fresh-faced guy from Kansas named James Grauerholz had gone to find him there. Grauerholz became, briefly, Burroughs’ lover, then his agent, editor, and his link to Lawrence.

“I mean he voluntarily came here, but I lured him,” admits Grauerholz. “And it was a plan to get him away from New York - the fame, the media, the thrill seekers.”

And to get him away from the heroin those “thrill seekers” regularly brought by, and the high rents. Grauerholz had already introduced Burroughs to his circle of outlaw writers, artists and musicians back in Lawrence, and that group took to Burroughs right off, and he took to them.

“There’s something called the genius loci, which means the spirit of a place,” says Grauerholz. “And he, within a year or two, became the spirit of the place.”

Burroughs jumps in

Burroughs got involved in the Lawrence underground right away. He quickly launched collaborations with Lawrence artists like Phillip Heying, a photographer who was a freshman at the University of Kansas when William S. Burroughs came to town.

“On the one hand, it was very normal...just this guy I knew that was kind of eccentric,” recalls Heying. “And in other ways it was like all of a sudden having a volcano erupt, in your backyard.”

Heying and Burroughs worked closely on visual art pieces, using Heying’s photography. It was a partnership that lasted until Burroughs’ death 17 years later.

Burroughs also attracted some of the most influential and creative countercultural figures of the 20th century to rub elbows with locals.

“It was just stunning,” says Heying. “It was like this direct pipeline to a world of people and ideas that had radically changed culture.”

It would be hard to develop a complete list, but Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, Jello Biafra, Norman Mailer, and Kurt Cobain, came to visit Burroughs.

“I spent a fair amount of time and got acquainted with Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary,” says Heying. “I had a brief interaction with Hunter Thompson, just kind of got a good look at him and saw him in action.”

All of them came to a small bungalow in east Lawrence that William Burroughs had picked up for $29,000.

The town that let Burroughs be

Sitting at Burroughs' dining room table, Jim McCrary, a poet in Lawrence, recalls countless evenings spent here with “the old man.”

“I would come in and sit down over there,” says McCrary. "He’d say, ‘Jim, roll me a joint.’ I’d roll him a joint, light it, and hand it to him. He would take three hits and hand me back like an 1/8 inch of a roach. That was the funny old guy that I just could not help but love.”

A lot of people loved Burroughs here. Well, enough anyway. And McCrary says, he gave them good reason.

“He was a nice guy,” remembers McCrary. "You know like, if you came to his house, and you hung around and you left. He would always walk out on the porch, and wait until you got into your car. If he drove you home, he would wait, until you got into your door.

“He may have written or said or done some ungodly horrible things. But the things that stuck with people were things like that.”

McCrary says Burroughs was very comfortable because the rest of the town just let him be. Heying says the atmosphere in Lawrence allowed Burroughs to be very productive.

“Right up until the end of his life he was scribbling, at least, if not really working on something full on. And then the mountain of his visual art that he was working on every day with tremendous joy,” says Heying.

This is something, McCrary says, that the East Coast artists and writers have a hard time wrapping their minds around. Burroughs wasn’t “out to pasture” in Lawrence; he wasn’t a recluse.

“A lot of people, particularly on the East Coast, particularly in New York, think that he was taken away, and sequestered in this small, craphole Midwest town … and maybe that’s true. But, maybe that’s what he wanted,” says McCrary.

“William adopted Lawrence in 1982. It’s taken Lawrence longer to adopt William.” –James Grauerholz

Since Burroughs’ death in 1997, Lawrence officials have dedicated a creek, a nature trail, and even a playground to him.

“The fact that there’s a Burroughs trail is really cool. That fact that there’s a Burroughs playground, is a little bit ironic,” says McCrary.

After all, Burroughs wrote about sexual encounters with young boys, accidently shot and killed his wife, and took lots of drugs.

Not everyone here is so proud to of Lawrence’s association with William Burroughs. Jere McElhaney, was on the Douglas County Commission when the park, creek and trail were named. He spoke out stridently against honoring Burroughs over any number of local sports and business success stories. He’s softened his opposition, in the meantime.

“You know, the guy admitted he was a habitual drug user, some problems with alcohol, shot and killed his wife, I guess by accident, but something like that happened,” says McElhaney.

“I think we just have to be very careful sometimes who we hold up on the pedestal, even though their talents might be great,” he says.

Burroughs’ talents are the talk of Lawrence these days. His work is on display at the Lawrence Arts Center, and at the Spencer Museum, on the University of Kansas campus. Stephen Goddard, the Associate Director and Senior Curator at the Spencer says it’s only right.

“He was a very important and influential member of our community for many years, and it’s reasonable to acknowledge him on an occasion like this,” says Goddard.

Goddard says Lawrence, Kan., was instrumental to Burroughs’ visual art.

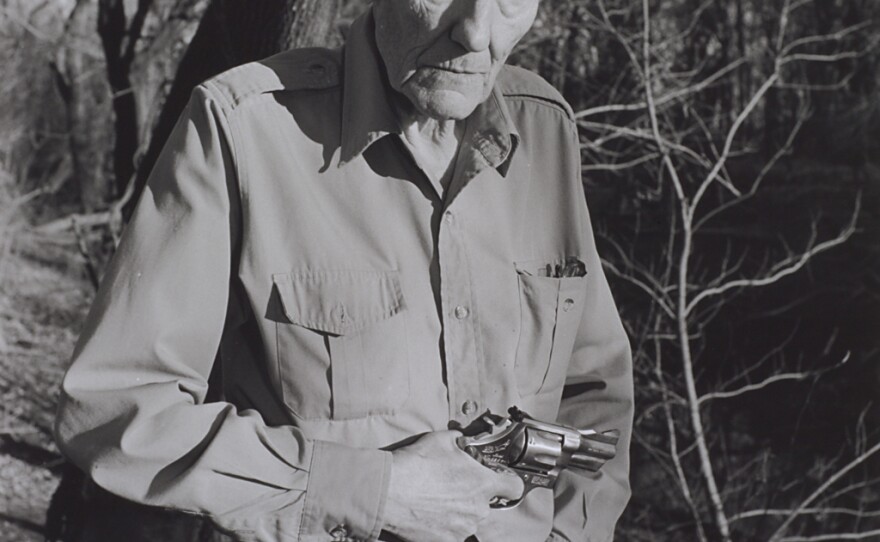

“One reason he was drawn to Lawrence was he could go in the country and shoot stuff, without getting in trouble. So the gunshot works, the doors, and all that kind of material, was specific to Lawrence,” says Goddard.

And James Grauerholz says that the qualities of Lawrence that made Burroughs at home still hold.

“And now,” says Grauerholz. “It is my hope that the fact of his association with Lawrence, will shine brightly, as a beacon, to indeed attract the different, and the strange and the alien and the intelligent and the daring, to this town, lest it turn into Topeka, or Overland Park.”

No offense to the good people living in the state capital, or the prosperous Kansas City suburb, but Grauerholz wants it understood that, in Kansas, Lawrence is the capital of weird, and William S. Burroughs still represents the genius loci.