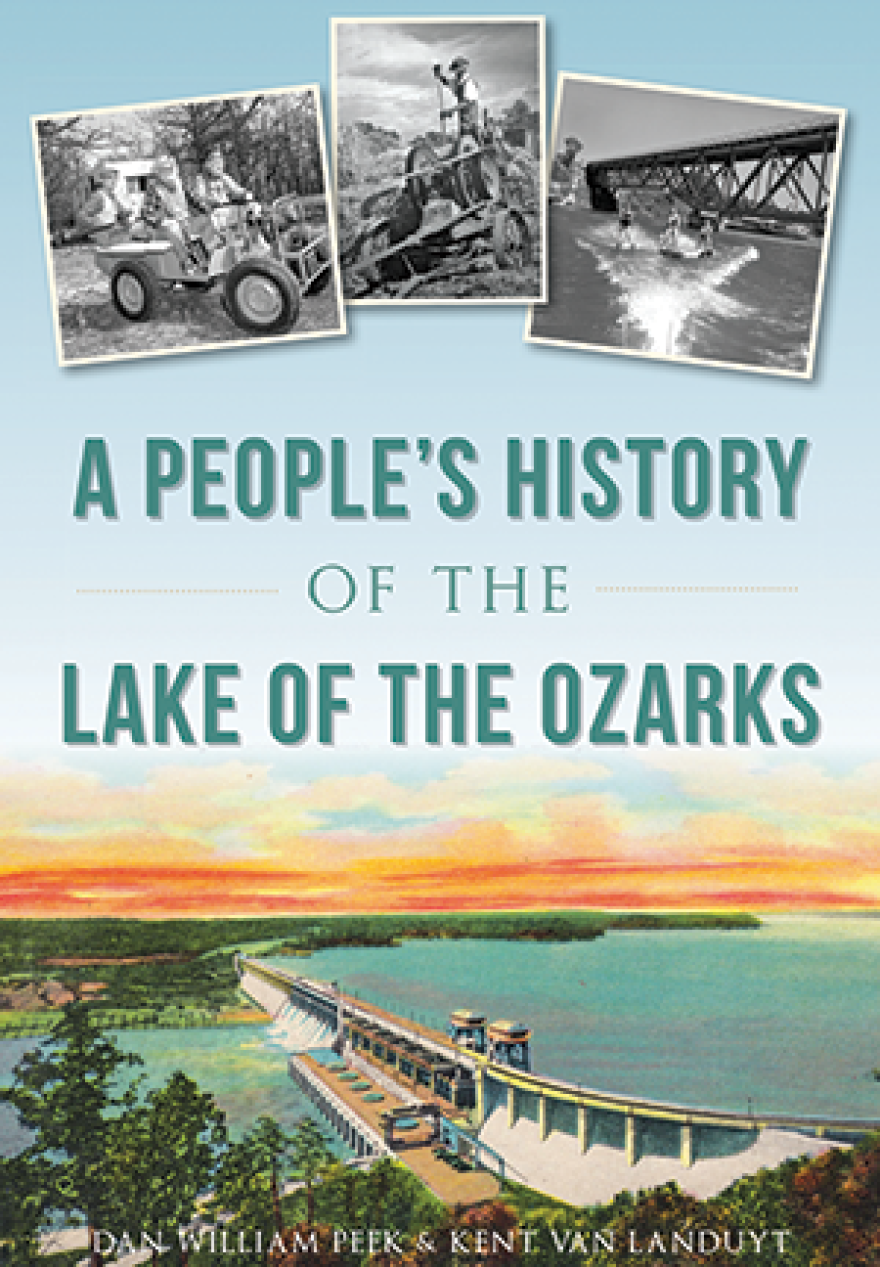

The Lake of the Ozarks is one of Missouri's most popular weekend getaways, which is what inspired Dan William Peek and Kent Van Landuyt to publish A People's History of the Lake of the Ozarks a couple of years ago.

The two authors say they hope that all visitors, true locals, newcomers or just weekend vacationers take the time to appreciate the lake not only for the amenities it offers today, but also for the nearly forgotten history that lies beneath the water.

Before 1931, when the Bagnell Dam was built on the Osage River to create what was then the largest man-made lake in the United States, people lived off the land on farms in a mostly cashless society, Van Landuyt says. There were a few small towns and some schools, some logging industry for the railroad and a drinking hole here and there, but that was it.

"The lake area was Missouri hilly Ozarks. Fairly country, or what people think of as the country hillbilly," he says. "The people did not have electricity at that time. There were not any roads. There were trails. They traveled by foot horse or on a wagon."

A Kansas City lawyer named Ralph Street first had the idea to build a hydroelectric dam on the Osage River in 1912. He was perhaps inspired by a similar project taking shape in southern Missouri, where the construction of a dam on the White River created Lake Taneycomo. That project was completed 1913.

Street started spending time in the North Central Ozarks, developing parternships with engineers, real estate negotiators and locals as he tried to pull together a plan.

But he didn't have the money to make the idea come to life until 1924. That's when he met and partnered up with Walter P. Cravens, the president of the Kansas City Joint Stock Land Bank, according to Van Landuyt and Peek.

The authors say Cravens had the idea to take foreclosed and bank-owned properties in Missouri and Kansas and trade them with people in the Ozarks whose land would be flooded by the dam.

At the same time, Cravens had created, and had shares in, other corporations that would also benefit from the deals, such as the Missouri Hydro-Electric Power Company and the Farmers Fund Inc. In 1927, Cravens was indicted for missapropriation of land bank funds and later sent to jail.

Street ended up taking a job with Union Electric, the St. Louis Company that would later complete the project.

Life before the lake

When surveyors and real estate developers from Kansas City and St. Louis started coming to the area talking about hydroelectric power, a dam, and a lake, local people didn't know what to make of it, the authors say. Many didn't believe that the dam would even hold water, or that their land would be affected.

Van Landuyt says some people in the area didn't completely understand the consequences of the deals they were making.

"People were really in disbelief and really hardly accepted the idea," he says, "until they finally were taken off their property or that their property had been purchased and they were made to leave."

While some locals did successfully sell their land and relocate, he says, renters, share tenants and squatters lost the most during relocation.

A new beginning

Many others, however, stood to gain during the Bagnell Dam construction. While the rest of the country was in the middle of the depression, the project brought in jobs and commerce.

Between 1929 and 1931, Union Electric hired more than 20,000 people at an average rate of 35 cents an hour; on average, 4,000 people would be employed at any given time. The influx of workers and their families from different places created the need for lodging, schools, stores and other services.

The project was completed in May 1931. Visitors came from all around the region to watch the reservoir fill up. The new lake created 1,150 miles of shore line.

Unlike a typical Army Corps of Engineers flood-control lake project, this lake was a private project, so the shoreline around the lake was open for development. In the early days, visitors were mostly recreational fisherman and boaters. People purchased small lakside cabins or visited for holidays.

An urban lake?

The lake's popularity and development around it have continued to grow.

Peek, an Ozark local and self-described hillbilly, says you can feel the effects of this new urbanization all around the lake.

"The west side is the Kansas City side, and the east side is the St. Louis side," he says.

"The Kansas City side is more of a laid-back, slower routine. The east side is: 'Hurry up go go go, get out of the water, go waterski, hurry up, we gotta go eat' type of thing. There is a definite different style in serving those types of styles."

Peek says the popularity of the lake and the region created some resentment.

"Our families go back way beyond when the lake was created," he says, "so there's still this idea of us and them. The newcomers and the true locals."

But Peek and Van Lunduyt say true locals and newcomers alike are at risk for losing the history of their region in the depths of the lake and the development surrounding it.

"We were born in 1945, so the lake had been there for 14 years," says Peek. "For Kent and I, and other people of our generation the lake was just there."

Peek says even he didn't know the full story behind the Lake of the Ozarks when he was growing up. As he got older, it was that realization of how fragile stories can be if they're not told that inspired him to make sure this one was not forgotten.

Dan William Peek and Kent Van Landuyt told their story to KCUR's Gina Kaufmann on Central Standard. You can hear the conversation here.

Suzanne Hogan is a contributor for KCUR 89.3. Email her at suzanne@kcur.org.