Channy Chhi Laux is an American. She earned two undergraduate degrees from the University of Nebraska and a master’s from the University of Santa Clara in California. Laux’s son is an Eagle Scout, and her daughter has nearly finished a doctorate at the University of Southern California.

Her list of American-sounding accomplishments is long, including working as an engineer in Silicon Valley for 30 years and starting a specialty foods company called Apsara.

Before building this life, though, Laux had to flee the Khmer Rouge, whose genocidal takeover of Cambodia in the 1970s wiped out two million people, including Laux’s father and little brother.

Laux visits Kansas City to tell her story on April 6 as part of the First Friday lecture series, which is open to the public, at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

UMKC professor Andrew Bergerson extended the invitation. He teaches history and public humanities and specializes in the history of everyday life with a focus on modern Germany, and he directs the Certificate in Holocaust and Genocide Studies. He says it’s important for students as well as community members to hear details of genocides straight from survivors’ mouths.

“Particularly for the students involved in the Certificate in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, it is a real benefit to their understanding to meet personally with the victims and to learn more about less-well-understood genocides,” he says.

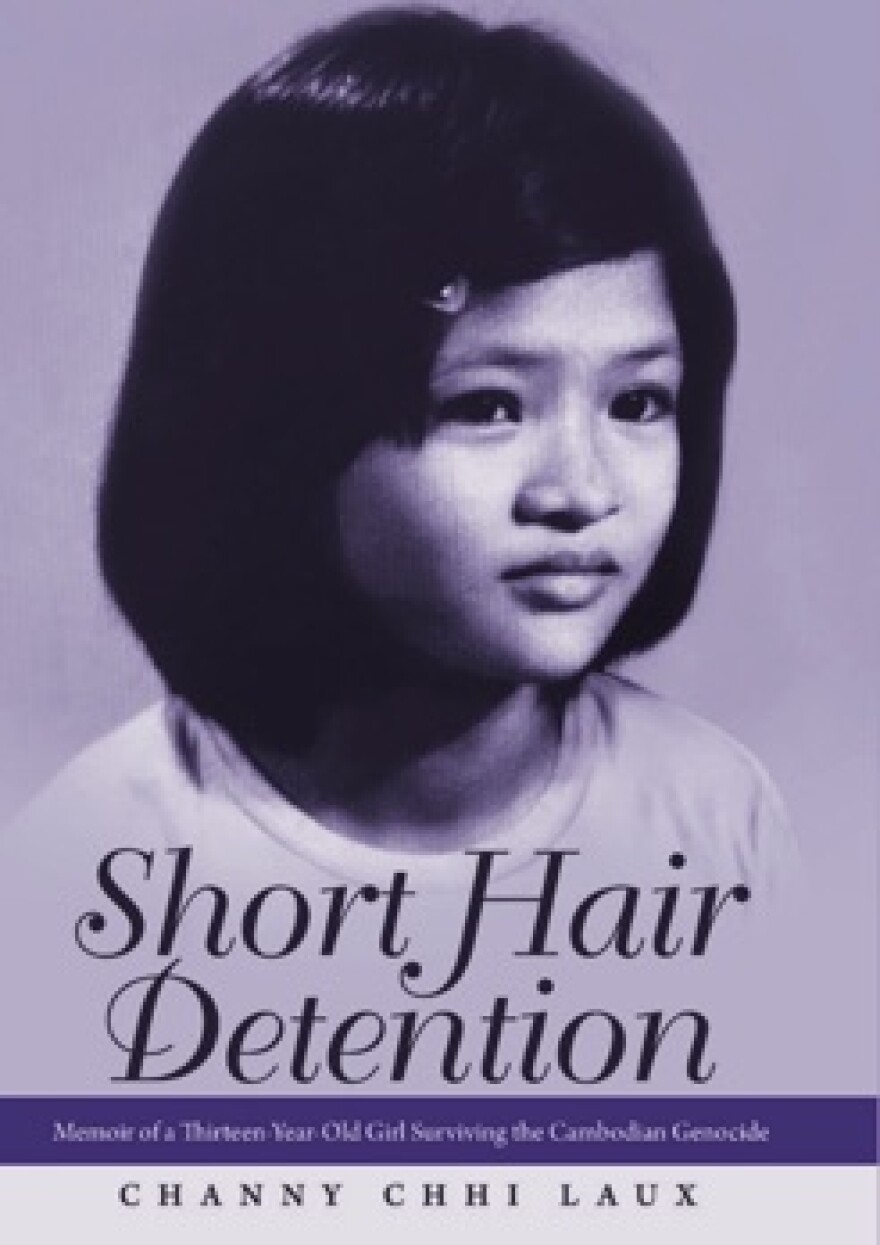

Laux has recently published a first-person account of her life from April 1975 through her escape, assisted by UNICEF and First Lutheran Church, in June of 1979. She titled it "Short Hair Detention" after her captors’ controlling insistence that long hair would get in the way of the manual labor she was expected to perform.

As Laux tells it, she was a happy, middle-class 13-year-old studying for a middle-school placement exam. After her first day of seventh grade, she and her family were herded on foot into the unfamiliar countryside where the “Black Uniforms,” as she calls the Khmer Rouge, starved them and made them work in fields covered by waist-high, leech-infested water.

The goal of the Marxian communist Khmer Rouge regime was to create a classless agrarian utopia, one that eliminated intellectuals and celebrated rural people and farmers.

Laux quotes her father, who initially ran an import-export business, as saying, “We replaced cows with humans to work the fields, while the rest of the world was replacing animals with tractors.”

When her first child was born in 1992, Laux began writing. She wanted her children to know, blow by blow, what their mother had endured: that she survived largely on thin rice soup and critters she gathered in her pockets, like snails and tiny crabs; that she was sexually assaulted; that her love for her own mother repeatedly renewed her determination to survive.

Writing those details was not easy. She conferred with her siblings to fill holes in her memories, reliving much of the torture together.

The more she wrote, she says, the braver she felt. What initially was meant for her family gradually became a story she wanted to share with others. She eventually decided to self-publish with a house run by Simon & Schuster.

“The more people know about it, the more we have the chance to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” she says by phone from her home in Fremont, California.

Upon publication of her book in December, she visited her old high school in Nebraska and met with students, a mix of refugees and immigrants.

“When I shared with them my story some of them started to cry,” she says.

She says the school seemed just as welcoming to the now larger number of foreign-born students as it had in the late 1970s, but she understands that newer immigrants have fewer opportunities now than she and her family did.

They also don't receive as much aid.

“When I came here everything was ready for me,” Laux says. “I can’t imagine the refugees here right now — if they don’t feel they’re welcome at all, I can’t imagine how terrible that must feel for them.”

Regardless of their level of aid and community support, Laux says she still fully identifies with the many challenges immigrants face. Those include cultural differences in dating — the children are in one culture, yet the parents are still in another.

And parents, having survived great hardship, sometimes find it difficult to see beyond basic needs in order to prepare children for success. Laux says that a parent may be inclined to say, “What else do you want? You have food. But that’s not enough.” The entire family has so much to learn if they are to flourish — and their drive needs to be extraordinary.

She largely credits her own success to a silent vow she made to her mother, whom she calls “Em,” during the genocide.

Just after her father and brother’s attempted escape, she writes, “I promised myself that if I ever made it out of there, ... I would take care of Em as much as I could, no matter what. ... ‘Dear God, please help me to be a strong person and guide me down a path so I can provide and care for my mother.’”

Having now put her story on paper, she says it’s becoming just that: a story. She likens it to a thorn that disappeared into her finger while she was living in hell. The experience and the thorn will continue to be a part of her, but now neither one bothers her as much as it once did.

When she finally saw her young face staring back at her from the cover of the book, she couldn’t help but cry.

“I cried so much in the shop because I felt sorry for her,” she says. “She’s not part of me anymore but I know everything about her and all the things she had to go through.”

Channy Chhi Laux, 1 p.m. on Friday, April 6 at Room 215 Cockefair Hall, 5121 Rockhill Rd., Kansas City, Missouri 64110.

KCUR is licensed to the University of Missouri Board of Curators and is an editorially independent community service of the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Follow KCUR contributor Anne Kniggendorf on Twitter, @annekniggendorf.