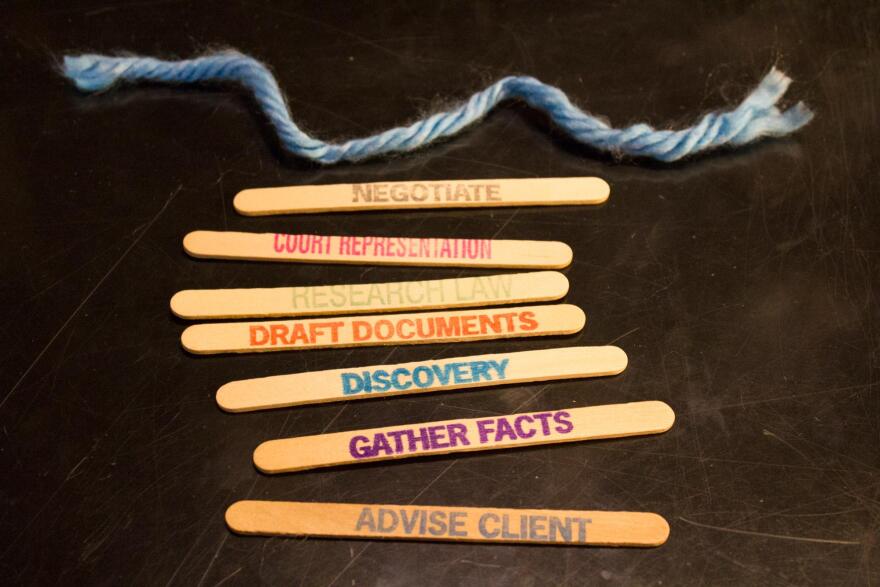

At The Law Shop in Van Meter, Iowa, attorney Amy Skogerson untied a piece of blue yarn from around a bunch of craft sticks. Each stick had a word or short phrase stamped on it, and she read from them as she placed them on her desk: “negotiate, court representation, research law, draft documents.”

These are all examples of legal services than can be unbundled from a larger package, a method that’s gaining traction in rural areas, where there is a shortage of lawyers. Also known as a la carte or flat-fee, unbundled legal services offer clients a middle ground between having no help and hiring a lawyer for an entire case, though some attorneys question whether clients are getting what they deserve — and whether it’s a viable way to earn a living.

Nationally, 60 to 80 percent of people don’t use legal representation for things like divorces, Skogerson said. It’s a trend she and her business partner, Andrea McGinn, noticed happening locally.

“And we started asking why that was,” she said.

The reasons vary, but include being unable, or unwilling, to pay a hefty fee, living too far away from an attorney to establish a relationship or just wanting to be self-sufficient.

Taking it apart

The idea of offering unbundled legal services goes back to the 1990s and a California family law expert, Forrest Mosten. It’s taken some time to catch on, but now, he said, technology can pair nicely with local services.

“Where unbundled services could be obtained via a phone or Skype or (Legal) Zoom, and it would save somebody a long trip into a more urban setting, I think it makes that service even more important and accessible,” Mosten said.“That's what we're looking for is legal access.”

It was at a one of Mosten’s workshops that Skogerson picked up the bundle of sticks she uses to illustrate unbundling. Mosten said Skogerson and McGinn are helping spread the concept into rural areas, where he said it “works particularly well.”

“Because many of those areas are under-lawyered, and there aren't as many choices, and people are often self-reliant,” he said.

There’s much they can do on their own, and then when they are ready and know what they need, a lawyer can help them finish.

In practice

After some training and initial cases, Skogerson and McGinn decided to make unbundled services their standard way of doing business. Take a divorce, for example: If the client only needs help with a child custody worksheet or electronic filing, the lawyer will quote a price for exactly that.

However capable people who choose to represent themselves are, McGinn said, they’re overwhelming the courts and sometimes just need a little help that is easy enough for a lawyer but daunting for someone without the legal knowledge.

“By giving those people the option of having an attorney for just part of their case,” McGinn said, “it's going to make such better outcomes for their families and their kids moving forward.”

When Jennifer Genovese was getting divorced in Adel, Iowa, several lawyers there and 30 minutes away in Des Moines gave her quotes of about $5,000, including mediation, court appearances and other things she didn’t need.

“My husband and I at the time were getting along, so we wanted a fairly smooth, quick divorce,” she said. The price tags were so intimidating, she said she and her then-husband looked into divorcing without a lawyer.

“I even printed the paperwork online, to do it ourselves,” she said. “And it was just — it was way too confusing.”

A local banker recommended she call Skogerson. Genovese and her now-ex met with Skogerson a couple of times.

“She's the one that filled out that paperwork for us, which made our life so much easier, and she did all the legwork,” Genovese said.

Plus, the cost was a quarter to a third of those early estimates, Genovese said, and her divorce was final in five weeks.

Genovese didn’t have to go too far, but people who live in rural areas in the Midwest and Plains states might be hours away from an attorney. Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota are among the states whose bar associations are actively trying to address legal access for rural areas.

And where there are still attorneys in private practice, many are looking to retire.

“As we're seeing fewer and fewer attorneys locate in rural communities, that access to justice issue is becoming more evident,” said Jennifer Zwagerman, the director of career development and associate director of the Agricultural Law Center at Drake University Law School.

She’s launching a program to connect rural communities with students and recent graduates. Offering unbundled services might help someone get a practice started, Zwagerman said, but she cautioned it poses particular challenges for inexperienced lawyers.

“One of the hardest things for a younger, newer attorney starting out with that type of flat fee or unbundled is figuring out exactly how long it takes to do certain things,” she said.

McGinn got her start fresh out of law school working as a solo practitioner in Skogerson’s building, with the more experienced attorney providing mentoring and guidance. Now, the two partners are expanding their office space so their practice can grow. A 2018 law school graduate will occupy one of the new offices, and they are gearing up to provide trainings for other lawyers who want to incorporate unbundled services.

Skogerson and McGinn emphasize that it can be part of a practice rather than the exclusive or primary focus. Their main goal is to help fill the growing rural access gap.

“We became lawyers to help people,” Skogerson said, “and if this allows us to help more people, then we're going to do it.”

Amy Mayer is a Harvest Public Media reporter based in Ames, Iowa. Follow her on Twitter: @AgAmyInAmes