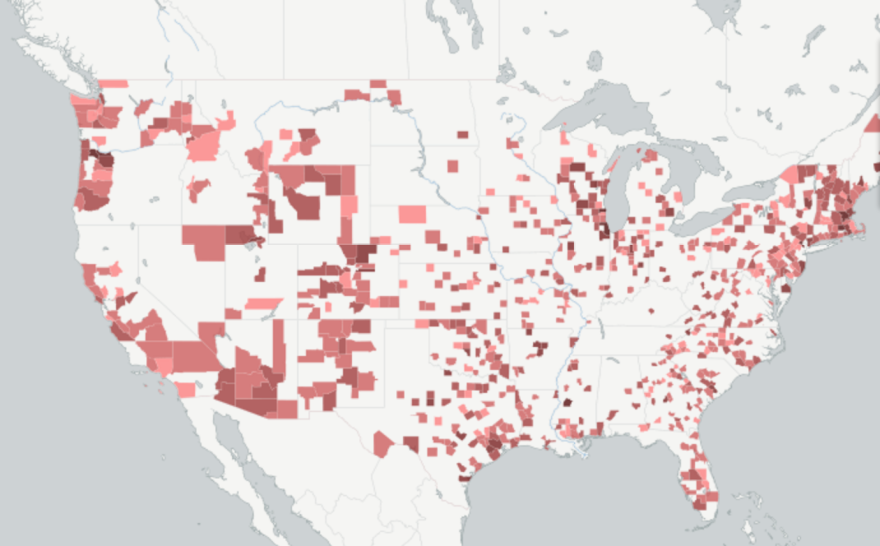

A new report from the Natural Resources Defense Council says more than 5,000 public water systems — including 68 in Kansas — are in violation of Environmental Protection Agency rules meant to protect people from lead in the water they drink.

Erik Olson, a health programs director with the council, a nonprofit international environmental organization, said those are just the systems that have been flagged. Many others — like the troubled Flint, Mich., system — don’t show up in the federal database.

“We are very concerned about severe under-reporting and gaming of the system by some drinking water suppliers to avoid finding lead problems,” he said during a Tuesday call with reporters. “In other words, basically a water system can avoid detecting lead in their water if they’re savvy and understand how the rules work.”

Olson said some systems test only in locations where they’re unlikely to find a high lead level — a tap that’s not served by lead pipes, for example.

“Some utilities have tested just in their employees’ homes, rather than targeting the high-risk homes that they’re supposed to do,” he said.

Other strategies Olson cited:

- Flushing all water from the pipes before taking a sample, to get rid of water that lead has leached into from lead plumbing.

- Removing the aerator from a faucet to get rid of lead particles that may have been captured in the screen.

- Using sample bottles with very narrow openings, so that the flow rate has to be minimized during the test. Faster water flow is more likely to disturb lead particles in the pipes.

“EPA finally, on February 29, issued a guidance document saying that water utilities should stop using three of the most widely used techniques, sort of tricky techniques, to avoid detecting lead,” Olson said. “EPA had known about these tricky techniques for many years, and there had been a lot of pressure on EPA to stop them, but the agency had not moved aggressively to stop water systems from using them.”

The report found that between 15 million and 22 million people nationwide have lead pipes bringing water to their homes from the water mains buried beneath the streets.

“It’s basically like sipping water out of a lead straw,” Olson said.

And enforcement of existing lead standards is lax. Almost 90 percent of water systems violating the rules never face any kind of formal enforcement action from state or federal agencies, according to the report. Only 3 percent faced any penalties.

“Basically, there’s no cop on the beat. We don’t have anyone making sure that the law is being complied with,” Olson said. “The bottom line is that providing safe drinking water to citizens is a fundamental government service. If you’re not doing that, you’re not doing your job.”

The report said water systems in 18 Kansas counties were cited for exceeding allowable lead levels.

The highest lead level reported in Kansas last year was at the Sundowner West Mobile Home Park west of Salina. While the federal limit for lead in drinking water is 15 parts per billion, one sample at Sundowner West contained 647 parts per billion. Officials with the Kansas Department of Health and Environment are leading an investigation after tests by local doctors this year found elevated lead levels in the blood of 32 Saline County children — most of them from Salina.

The report cited two Kansas water systems — the City of Mullinville, a small town in Kiowa County, and Saline County Rural Water District 7 — for health violations, which means they failed to take required steps to protect their customers from lead.

Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, said the report highlights an important public health issue.

“Flint, Michigan, was a wake-up call for America,” he said. “Once we saw the terrible outcome in that city when gross negligence or worse led to children and many others being exposed to high levels of lead in their water, people started looking around, saying, ‘What about my water?’”

Durbin is co-sponsoring a bill called the Copper and Lead Evaluation, Assessment and Reporting Act that calls for the EPA to develop ways to improve reporting, testing and monitoring of copper and lead in drinking water.

Bryan Thompson is a reporter for KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.