When Alvin Brooks told his father that he wanted to be a police officer, his dad’s first response was, “Why do you want to get into that mess? You know how they treat us.”

Brooks was determined. He became one of Kansas City's few black officers in 1954.

From there, over a long career in law enforcement and politics, he would also be a detective, civil rights activist, city council member, and mayor pro-tem. As he's about to turn 86, Brooks told host Gina Kaufmann on KCUR’s Central Standard, he's been reflecting on his life while writing his memoir.

His story starts out in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he was born to a 14-year-old mother and a 17-year-old father.

His mother had been sent to live with her elder sister in Little Rock, but she didn’t get along with her adult brother-in-law. The Brooks family, who lived across the street, let her live with them and then adopted him.

They moved to Kansas City when his adopted father killed a white man in 1933 in an argument over a moonshine still.

“It was rumored that … my dad had the best moonshine in Pulaski County,” Brooks said.

According to Brooks, the man contended that his father was stealing customers from other moonshine dealers in the county. He came to the Brooks house, firing his shotgun as he approached. Brooks’s father shot back through a thicket, killing the man. He was arrested but not charged. The sheriff, who was on the elder Brooks's payroll, told him to get out of town.

They came to a segregated Kansas City.

When Brooks was about 10 years old, his father rented a house in what Brooks described as a poor white area off of Linwood and Brighton. After fighting with the other neighborhood boys, Brooks became friends with them.

One day, the police picked up Brooks and his friends. A neighbor had called the cops because a group of boys had thrown rocks into her backyard, almost hitting her baby and her dog. When the police brought Brooks and his friends over to the neighbor’s house, she said they had gotten the wrong group of boys.

Brooks asked if they could go home. The officers, who were white, said no, and made them get in the car. As they drove, they told Brooks’s friends that they shouldn’t be with him, calling him the n-word and saying that “whites don’t associate with them.”

They stopped at Brighton Hill and told the kids to get out. One of the officers, who had been drinking, pulled out his gun. He told Brooks that he if could run over the hill before he killed him, he’d be free.

The officer cocked his gun.

“I’m just backing up, crying and pleading,” Brooks recalled. “And (my friends) were screaming and hollering, ‘Don’t shoot Alvin!’”

All of a sudden, his friend Billy, who was the youngest at 6 or 7 years old (the rest of them were around 11), jumped on the cop’s arm. The gun went off.

“We just ran. The police officers jumped in the car and left,” Brooks said.

About 10 years later, as a sophomore in college, Brooks decided to become a police officer — despite other such incidents.

He had become friends with a Jewish man he met at Fellowship House.

“We had this game that we played at one of the drugstores at 31st and Prospect,” he said.

Brooks couldn’t eat at the counter, so his friend, along with two other white people, would go in and order food for four. By the time the food came out, Brooks came in and sat with them.

“The game was, ‘How fast could we eat before the manager came by and told me to get out?’” he said.

“That’s the way we started social consciousness. And then, I think that social consciousness moved me to where, maybe if I got on (the police force), I could at least help make things a little better. And that’s been … my life for the last 60, 70 years.”

When he joined the police force, he said, black offers were relegated to just two districts in Kansas City.

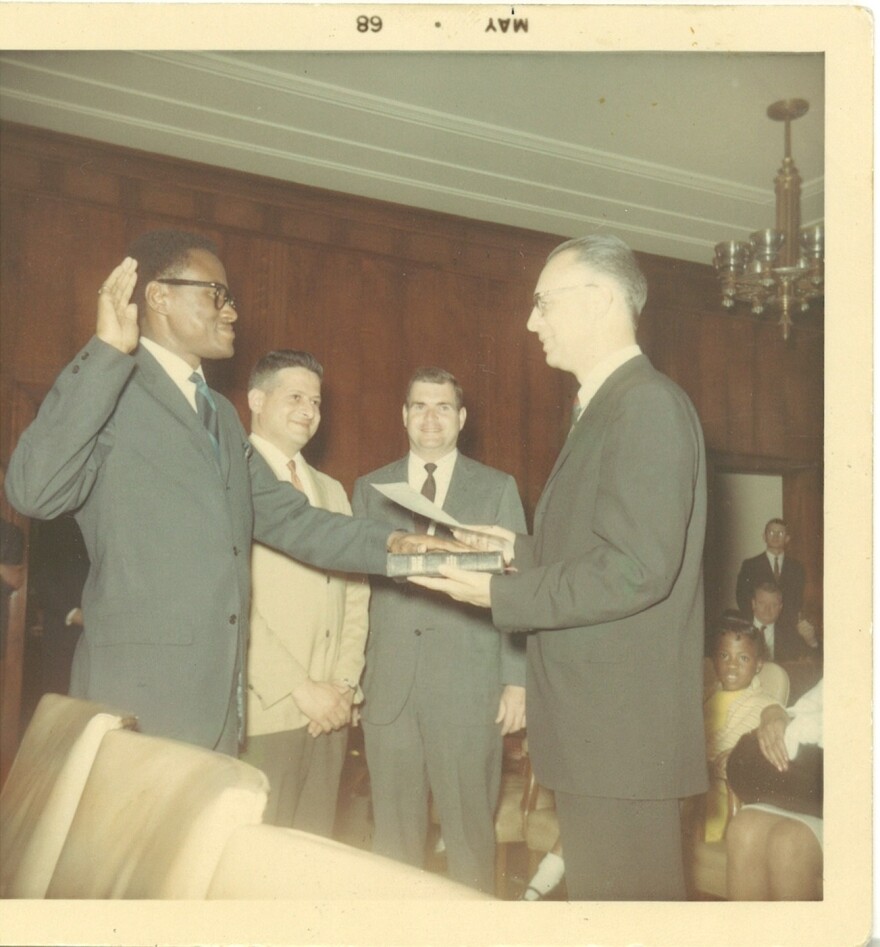

He worked in the police force for 10 years and left in 1964. From there, he worked in the Kansas City school district's Department of Urban Education. After the 1968 riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., he set up the human relations department for the KC government, then he was promoted to assistant city manager in 1972.

He retired from the city in 1991. Along the way, he had started the Ad Hoc Group Against crime in 1977, and he went full-time after his retirement. Elected twice to the Kansas City council, he served from 1999 to 2007 as the representative for the 6th District At-Large and as mayor pro-tem at the same time.

He was appointed by then-Governor Jay Nixon to the Board of Police Commissioners in 2010 and was its president for two years. Last year, he stepped down as police commissioner to serve on the school board of Hickman Mills.

His term was up, and he knew that Governor Eric Greitens wasn’t going to re-appoint him, he said. He wanted to move on.

“I had promised my late wife and my five daughters that the Board of Police Commissioners was my last political public hurrah,” he said.

But he also knew the Hickman Mills School District faced difficulty with its accreditation and the high rate of mobility among its students, of which 90 percent are African-American, he said.

“I figured I had gone to court enough — both family court as well as adult court — and seen the number of young African-American males being incarcerated,” he said. “The lack of education was a pipeline to prison and to the juvenile and the criminal justice systems.”

He said he remains an optimist and says a prayer every night: “Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.”

But he added an addendum, after a friend wondered what happens if you wake up.

“So now I say all that, then I say: ‘God, if I should wake up, please help me do something that would be pleasing to you in helping someone along the way.’”

He had much to be grateful for, Brooks said.

“I thank God for my wife and for my family and for what God has been to me in my life. And I hope that in my freedom of will that I’ve taken the high road and done the kind of things that God would have me do.”

Portrait Sessions are in-depth conversations with some of the most interesting people in Kansas City. Each conversational portrait is paired with photographic portraits by Paul Andrews.

Jen Chen is associate producer for KCUR's Central Standard. Reach out to her at jen@kcur.org and follow her on Twitter @JenChenKC.