Sam Shockley went to school with the black students who eventually desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. So he was more than familiar with the harshness of racism.

When he moved to Kansas City in the 1950s, he experienced a different brand of it.

“Here it was more covert,” Shockley says.

In the early 1960s, he and his wife began looking to buy a home in which to raise their family. Even with four years in the Air Force and working two jobs – at Ford Motor Company and at TWA – his good income wasn’t going to buy him a house on the wrong side of the color line.

“My salary and my ability to earn was equal to the white guys but I just couldn’t use it the same way,” Shockley says.

This year is the 50th anniversary of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The law prohibited discrimination by making it illegal to refuse to sell, rent to, or negotiate with any person because of that person’s inclusion in a protected class, such as race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status and national origin.

But the Fair Housing Act is not retroactive, so any housing policies – legal and institutional – would have impacted anyone buying a house before the act went into effect.

Among the practices that were in effect before the housing act became law were redlining, racial covenants, and blockbusting.

KCUR used The Kansas City Star's archives to examine a sampling of homes listed for sale in July 1963 – four west of Troost Avenue, four east of Troost Avenue. Troost has been commonly known as the racial dividing line in Kansas City, where white residents lived west of Troost and black residents lived east of Troost.

Back in 1963, the prices for all of these homes ranged from $10,500 to $17,750.

In 2018, according to Zillow, the list prices for those same homes ranged from $45,017 to $363,222.

The lower-valued homes are east of Troost, the higher priced homes west of Troost.

Clicking on the map below shows that properties on the east side of Troost saw modest appreciaton, while the value of properties west of Troost grew dramatically.

For example, a home on East 72nd Terrace was listed in July 1963 for $16,900; it is now valued by Zillow at $63, 493. Four miles away on West 72nd Street, a home selling in July 1963 for $16,950 is now valued by Zillow at $273,187.

Past practices of redlining, blockbusting neighborhoods and racial covenants lay the groundwork for why Kansas City is considered by today’s experts as not just segregated, but a hyper-segregated city, says Stephanie Frank, an urban planning professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

“Redlining is the denial of mortgages or other loans to a spatial area, neighborhood based on race. It’s not credit worthiness. It’s not on your ability to pay, “ Frank says. “It is specifically blocking people from borrowing money based on the color of their skin.”

Racial covenants were contracts imposed in deeds to prevent home owners from selling their property to particular groups of people, such as black people or Jewish people.

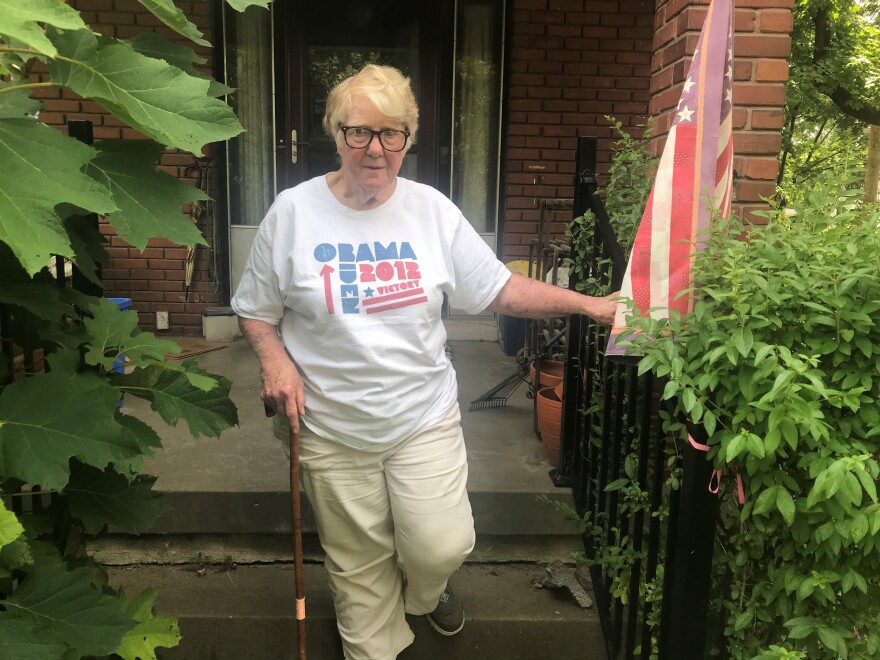

Margaret May and her husband were among those black families buying a home before the law changed.

“There were parts of the city that would not sell properties to black people,” says May, the former executive director of the Ivanhoe Neighbor Council.

May thinks the Brown vs. Board of Education desegregation case caused some blacks to move to better neighborhoods in pursuit of better schools. That change also triggered white fear. Within two years, her almost all-white neighborhood was all-black.

“Literally I’m told that a realtor would put a house up for sale and if he could sell it to a black person, then he would go to the other houses on the block and say you’re going to need to move because black people are moving in,” May said.

Frank, in her research, confirms May’s understanding. That common discriminatory tactic was called blockbusting. It was used to contribute to the declining values of black neighborhoods. For example, the home the Mays bought for $9,000 in 1960 was sold by them for about $70,000 in the late 1980s, but is now valued on Zillow for about $40,000.

“Preying on fears, white people’s prejudice and their fears of what’s going to happen to their property values so people would sell. And then they would turn around and then sell it at a predatory rate to a black family,” Frank says.

The discriminatory policies of Kansas City developer J. C. Nichols, such as the promotion of racial covenants, didn’t just impact the racial distribution of neighborhoods in Kansas City, according to Frank, but was influential on discriminatory housing policies nationally.

Danyelle Solomon researches race and ethnicity policy for left-leaning think tank Center for American Progress. She says home equity contributes to the accumulation of wealth in this country. So nationally, over time, discriminatory housing polices impact the black-white wealth gap.

“Today, black families have a wealth of $1 for every $10 white families own and a lot of that is rooted in housing policy. So, wealth is the measure of an individual or family’s net worth,” Solomon says.

Solomon's research connects the legally-enforced racism of the past to the current circumstances of today.

“While redlining is no longer legal, it has lasting impact. Redlining prevented black families in the 60s and the 70s from building real wealth,” Solomon says.

Mary Louise Byrne is a white woman who bought a home in 1961 in the Volker neighborhood. She never thought at the time about what options she had that other people didn’t.

“What I think is strange, and I’ve talked to friends about this, it never occurred to me when I was a teenager that there weren’t any black people in school,” Byrne says. “It was even on my radar.”

She said the decision for her and her husband at the time was just finding a nice place they could afford to raise their family.

The same priority held by Sam Shockley. Just with added considerations.

Shockley and his wife wanted to tell their children about discrimination to prepare them for the world while providing them the best head start they could. They could have moved closer to his jobs near the airport, but they just weren’t willing to risk being one of the few black families in a neighborhood.

“My wife and I both being from the South and having gone through the discrimination part we were just leery about going through it again and we just didn’t want to put our children through that. But we did want them to have a normal life,” Shockley says.

Regardless of which side of the city they lived in, Kansas Citians in the early 1960s sought the same things for themselves and their family. Decades later, the investment didn't always lead to the same return.

Michelle Tyrene Johnson is a reporter at KCUR 89.3 and part of the public radio collaborative Sharing America, covering the intersection of race, identity and culture. This initiative, funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, includes reporters in Kansas City, St. Louis, Hartford, Connecticut and Portland, Oregon.