H.C. Palmer had graduated from medical school but hadn't yet finished his residency when the Army drafted him in the mid-1960s.

President Lyndon Johnson's administration took 1,500 men from medical training programs across the country and sent them to Vietnam as surgeons.

By August 1965, Palmer found himself in a war zone as part of the First Infantry Division. All these years later, he says he’ll never completely find his way out — nor will others who’ve been similarly exposed to the “many horrific things that happen in war,” he told me in a recent interview.

But his life continued. For 47 years he worked as a physician, 18 of those in Kansas City. He had children and grandchildren.

Then, 10 years ago, he began writing poetry. At first, it was just for himself. Then, in 2014, he and Cindy McDermott of the Moral Injury Association of America founded the Veterans’ Writing Workshop of Kansas City. Their hope is to create a safe space where veterans and their families can regroup and process the harm done by their service through writing.

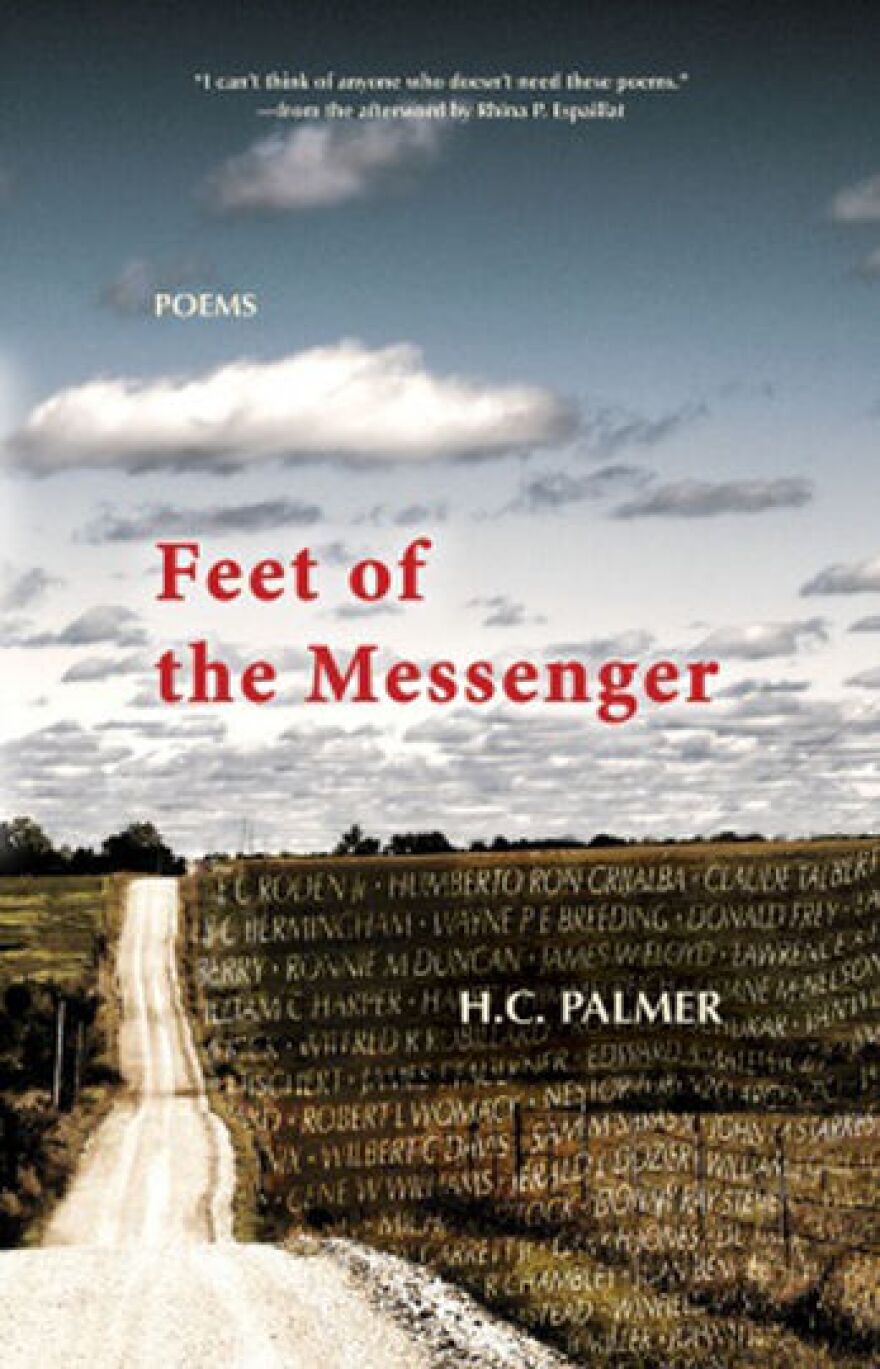

Palmer’s debut poetry collection, “Feet of the Messenger,” was published in fall 2017 by Kansas City’s BkMk Press.

KNIGGENDORF: I think you’ve said in relation to the work you do with area veterans, that moral injury is what they suffer from and what often keeps them from talking about their experiences in war. What do you mean by moral injury?

PALMER: To make it clearer, I think, I’ll compare it with guilt. For instance, when you’ve made a mistake or hurt somebody and you feel guilty about it, you can go ask for forgiveness, and usually if they give that to you, you’re pretty much over it all. But moral injury, especially in war — there are so many horrific things happen in war. You accidentally kill little children. And when you get to worrying about something you’ve done that’s so horrific, so bad, that you’re not just guilty, you feel such shame that you don’t feel like you deserve to be helped. Moral injury is actually the cause of almost all of the suicides from veterans coming back from war.

KNIGGENDORF: And poets who write about war seem to be a special breed — warrior-poets even in some cases. What’s been your approach?

PALMER: You know, I started writing poems 10 years ago and I did it for myself. The first poem in the book was a revelation to me; it just came from nowhere, that feeling. You can come to the writing of poems about war — some poems are obviously propaganda, like Brooke’s poem about WWI, where “How glorious it is that a little bit of you is buried somewhere in Europe and England is there as well.”

KNIGGENDORF: Great.

PALMER: That’s B.S., you know. Or you can come — I tried to come — as a healer and not as a warrior. I think everybody would come to it from a different direction as they read or write about it. The kind of poems, the kind of literature I don’t like about war, are about the heroic, glorious war battles. There’s never been such a thing.

KNIGGENDORF: In “Considering the Landscape,” the speaker in the poems likens the Mississippi rice farms he sees from an airplane window to the rice paddies of the Mekong River Delta. His seatmate says Vietnam was 30 years ago and this man, the speaker, should be over it. Did that exchange really take place?

PALMER: Yes.

KNIGGENDORF: I couldn’t help but wonder. Okay, it did.

PALMER: Yes, you know, so many poems are gifts people give you by saying something that may be stupid or may be the total opposite, there may be so much wisdom in what they say that they just hand you a poem and you’ve got to be smart enough — I try to be — to keep a little notebook with me so I never forget those things. There’s another poem in there, the third poem in “Five Notes on War,” that was a gift to me and my friend that I write about. We were at the Wall and it was cold and windy and there were less than 10 people there:

Last winter, at The Wall

again. Snowing & very cold.

It seemed we were alone

until a man & woman reflected

in the granite from behind us.

For a long time I watched

them inside the stone.

When I turned

I saw them weeping.

Do you have someone here? I asked.

Just the two of you, she said.

We had been at that particular panel on the Wall because my friend has six of his buddies who were killed on the same day, so they’re all together on the wall and he can actually touch them all at once with his hand. We’d probably been there ten minutes and we worried that we were keeping this couple from coming up there to look at somebody, some name they were looking for. But actually they were just watching us and it was a pretty dramatic moment.

KNIGGENDORF: Can we look at your title poem? It’s number VII in “Selected Notes on Beauty.” The speaker’s examining the foot of someone who’s back from a tour in Afghanistan and quotes Isaiah. Would you please read that?

PALMER: Sure.

December 14, 2010, the VA, continued

He tells me his boot was blown off by an RPG.

They were isolated five days in a valley called Korengal,

no LZ for a med evac so the medic dressed his wound

then commandeered a boot from a body bag,

searching four bags for one that fit. That boot

smelled of rotten flesh but was a gift from Heaven.

That boot and a little morphine let me stand to fight.

I take his good foot, compare side to side, before

and after, recalling a scripture, Perhaps these feet, I say.

He asks, What do you mean? And I say Isaiah—

it was Isaiah who said, How beautiful upon the mountains

are the feet of the messenger who announces peace.

KNIGGENDORF: Do you imagine a soldier might announce peace?

PALMER: Well, I think Eisenhower did in VE Day. And MacArthur did in VJ Day. So in that sense, they do.

KNIGGENDORF: And a common soldier now?

PALMER: I think the common soldier now would like to — would love to — announce peace. You know what, the common soldier has nothing to do with it, he just goes where they tell him to go and does what they tell him to do. They’ve trained him to do the unthinkable and it’s the job of the politicians to find some way to get them to go do the unthinkable for them.

H.C. Palmer and Kansas Poet Laureate Kevin Rabas read as part of the Thomas Zvi Wilson Reading Series, 6 p.m., Tuesday, April 17 at the Johnson County Central Resource Library, 9875 W. 87th St., Overland Park, Kansas, 66212.

Follow KCUR contributor Anne Kniggendorf on Twitter, @annekniggendorf.