We already know that the budget problems in Kansas are eating into some core functions of government.

The state will have to postpone maintenance work on hundreds of miles of highways. And those highways are a little less safe because the Kansas Highway Patrol is at least 75 troopers short of full strength.

But budget problems for state law enforcement run even deeper.

The Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) is turning away felony investigations because of a lack of agents.

Around these parts you don’t hear much about the KBI.

In northeast Kansas, most police agencies have their own detectives so when a crime needs investigating, it’s done by local police or sheriff’s deputies. But in much of the rest of the state, they call in the KBI.

"There is a large sector of Kansas that has a very limited law enforcement resource pool and it’s been our mission to support those areas," says KBI Director Kirk Thompson, who has spent most of his career with the Bureau.

How limited? Half of all law enforcement agencies in Kansas have fewer than five officers and 87 percent have fewer than 25.

That means many departments have no expertise in felony investigations.

Many felonies in Kansas, says Thompson, are going uninvestigated: "Of the 500 and some cases we took on last year, we declined well in excess of 100 case requests."

That means 20 percent of the cases referred to the KBI don’t get investigated because there’s not enough money to hire agents.

Right now, Thompson says, there are 71 investigators spread across Kansas. The KBI should have 93.

Thompson says the KBI has to focus on only four areas: homicides and serious violent crimes, sexual assaults against children, government corruption and drug traffickers with high levels of violence. Thompson says agents try to complete their investigations in just 90 days. It's not ideal, he admits, but the KBI is working within the resources provided.

"In order for us to make ends meet, if you will, that requires that we decline some cases that we normally would or should do," Thompson says. "We will not compromise on quality."

Let’s pause for a moment and talk about the history of the KBI.

It was established in 1939 to catch bank robbers and cattle rustlers, crimes local cops couldn’t handle. In fact, many of the early KBI agents had both law enforcement and ranching backgrounds.

At the time, local police and sheriffs had no authority outside of their home counties, so Kansas needed an agency that could investigate across county lines.

Its most famous case was in 1959. That's when KBI agent Alvin Dewey led the investigation into the murder of the Clutter family outside of Garden City. That case would be immortalized in the book and movie In Cold Blood.

The hallmark of the KBI is this: Swarm big cases with seasoned investigators in places where they don’t have them.

"It’s the smaller communities, the smaller counties, that really need some assistance because they do not have the expertise," says Sheriff Jeff Herrig of Jefferson County and president of the Kansas Sheriff's Association.

He says the KBI is being damaged by budget problems in Topeka.

"They need some agents," Herrig says. "It’s just like the Kansas Highway Patrol. We need to get them back up to staff."

Last legislative session the KBI asked for $1 million to hire 10 more agents. The governor and Legislature said no.

The KBI has also sought $200,000 to begin the process of replacing an aging computer system, a system that tracks every crime in Kansas.

Again, the governor said no.

The agency even had to block off part of its Topeka parking garage because there’s no money to fix the structural problem.

However, there is one area where the KBI is growing -- its new $55 million dollar lab on the Washburn University campus in Topeka.

There is a new, state-of-the-art gun lab where they test fire hundreds of weapons a year, for crimes ranging from gang murders in Kansas City to cattle killings in western Kansas.

There's a new toxicology lab that processes almost 4,000 cases a year, according to lab director Mike van Stratton. In addition, the KBI lab in Topeka and satellite labs in Kansas City and Great Bend handle fingerprints and DNA testing.

While the lab is beautiful and will attract talented techs, it’s unlikely they’ll stay.

The fact is that KBI pays poorly.

Director Thompson says the KBI spends about $191,000 training each of the forensic scientists at its labs.

"Once we get them to about the four to five year experience level, they are very, very marketable to other laboratories around the country and that's where we're not competitive," he says.

The same is true for investigators. The KBI pays its agents around $54,000 a year and requires six years of law enforcement experience including two years investigating felonies.

Detectives in Kansas City, Kansas, start at about $66,000 a year.

"It’s difficult for us to encourage people to come to our organization when the state right now has a history of no salary increases for a long period of time," Thompson says.

Thompson says he’s going back to the Legislature to again ask for more money to hire agents and raise salaries.

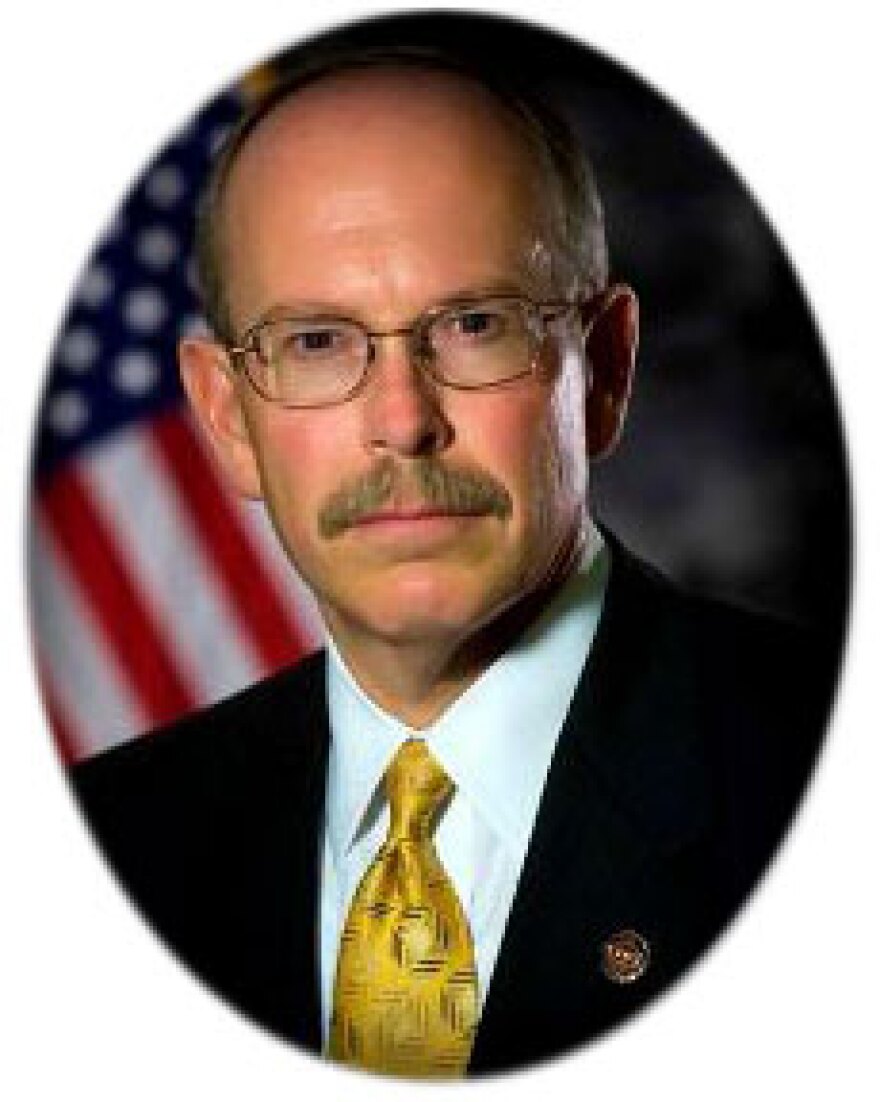

House appropriations committee Chairman Ron Rykman from Olathe says the KBI will get a fair hearing. "It does make sense to pay agents a competitive wage. As most government employees you’re not there for the money, you’re there for the public service but you also need to be fairly compensated for the work you do," says Rykman.

The reality is that the state has little money in the bank and monthly revenues are behind projects.

A bad sign, it appears, for Kansas state law enforcement.

Sam Zeff covers education for KCUR. He's also co-host of KCUR's political podcast Statehouse Blend. Follow him on Twitter @samzeff.