When Jennifer Myer looks at the photographs along the wall of her tiny museum next to the Lansing Correctional Facility, the experience is "humbling," she says.

Others who've seen the images say they're "haunting."

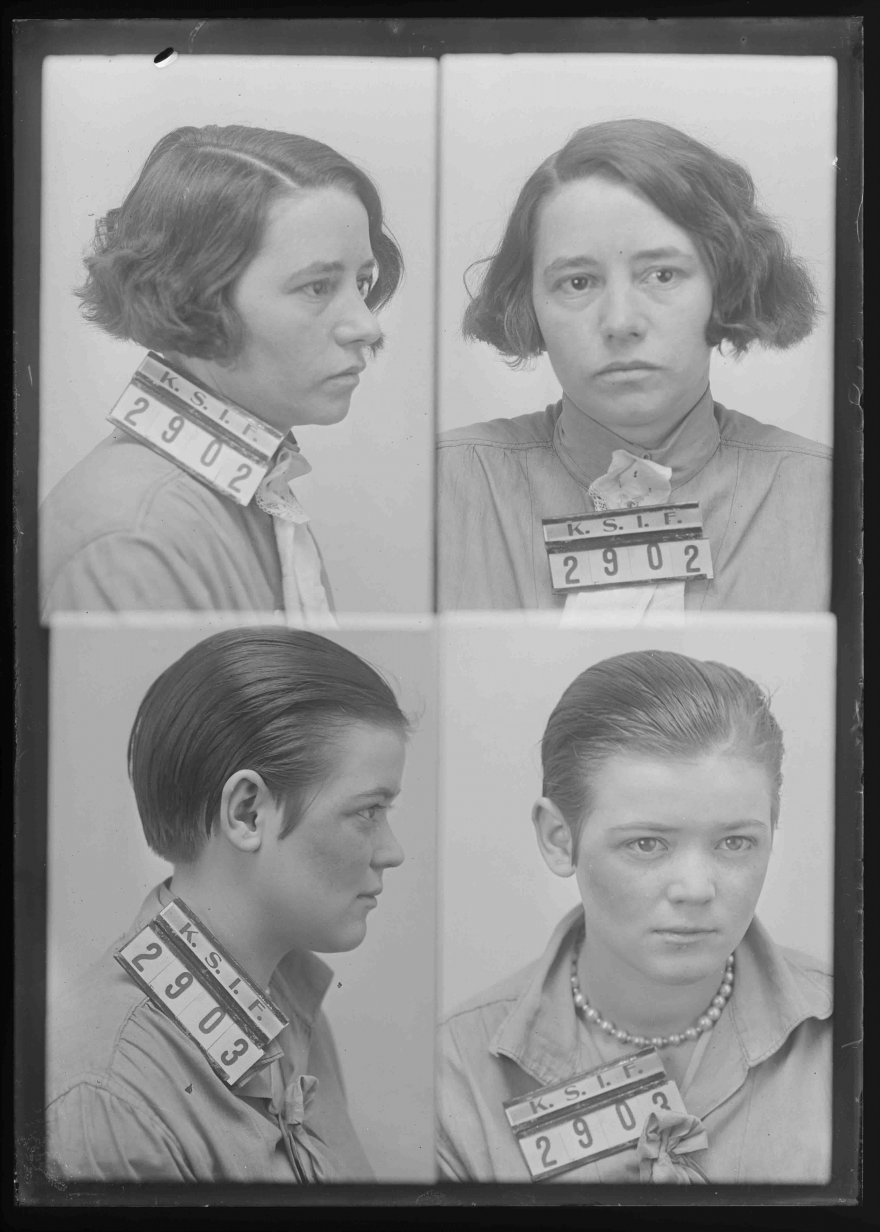

As the site supervisor (and the only employee) at the Lansing Historical Museum, housed in a tiny former train depot on the prison grounds, one of Myer's jobs is to preserve historical material associated with the hulking limestone fortress that used to be called the Kansas State Penitentiary. The prison opened 1868, so there's a lot of history — including an "intake" picture of every inmate.

A hundred years ago, some of those photos were taken with glass plate negatives. And when Myer secured grant funding from the Kansas Humanities Council to digitize sets of them from 1902 and the 1920s, the high quality of the resulting images was "astounding," Myer says.

"It’s hard to believe that these people lived so long ago that they’re now dead, have been gone quite a while," Myer says.

"There were lots of little details I thought were interesting," says Bryon Darby, who was an assistant professor of photo media in the department of design at the University of Kansas when he took digital photos of the back-lit negatives (he has since moved home to Utah).

"All we have is a face to look at, at least that’s all I had," he says. "There’s sorrow and desperation and these kinds of emotions you can read from a portrait."

But that was all speculation, he says, because he knew nothing about why the people were in prison. One obvious fact stood out, however.

"I was surprised by the number of women," Darby says, adding, "I was surprised by how young a lot of them seemed to be."

Myer wanted museum visitors to know more about the people in the pictures, so she spent a couple of afternoons looking through records at the state archives in Topeka. Once she figured out the inmates' home towns, she started looking through old Kansas newspapers to see if stories had been written about them.

"And for some of them," she says, "there were."

The women of the Kansas State Industrial Farm

Myer found write-ups for several of the men on one wall, who look like the sort of outlaws you'd see in any classic western movie. And she found articles about some women who were known as local characters.

And she found information about the young women Darby noticed, whose pictures now fill a wall of the old train depot.

"All of these women were picked up for lascivious conduct," Myer says.

But they weren't prostitutes. Consider the case of Carry Cox and Mary Walker.

"The Columbus Daily Advocate liked to report on mundane things," Myer says, likening the small-town paper's reports to the Facebook posts of today. "So it would be like, 'Mary Walker visited her cousin this weekend, out of town.' All the way up to the week prior, the newspaper was reporting on these two girls — they were teenagers — visiting family, going to local dances or doing things in the community. All of a sudden, there’s an arrest."

A doctor with the public board of health had initiated a raid on a dance hall, and Cox and Walker were arrested for violating something known as Chapter 205: a World War I-era quarantine law to help prevent the spread of venereal diseases.

"As the country was enlisting all these men into the Armed Forces, they found a pretty hefty portion of the population had syphilis or gonorrhea," explains Nikki Perry, who did research on Chapter 205 while earning a doctorate at the University of Kansas. "It was seen as major public health crisis but also a national security crisis, because they were concerned about keeping the troops fit to fight."

Chapter 205 gave public health officers wide discretion, Perry says.

"They could decide who was 'suspect' and who they could examine," she says. "They would detain women for a couple of days, examine them, do tests to see if they had diseases. The tests were really inaccurate, so if they thought she might be sexually active, that might be a reason to diagnose her with syphilis or gonorrhea."

By the time of their arrests, women such as Carrie Cox and Mary Walker wouldn't have been incarcerated in the big prison (where they risked assault by male inmates and other inhumane treatment), but at the nearby Kansas State Industrial Farm, an actual working farm where, social reformers believed, women stood a chance of being rehabilitated.

"The women’s industrial farm as a separate women’s prison opened in spring of 1917," Perry says, "and they only had around 17 inmates — it was a a very small number, because this was the typical female inmate population from the state penitentiary. Then Chapter 205 began to be implemented over the summer and into the fall, and by end of year there were almost 400 women at the facility."

That made Jennifer Myer wonder how many men had been incarcerated for violation of Chapter 205.

"I actually couldn’t find any," she says.

"It was enforced primarily against women," Perry explains.

Reading the short write-ups of the inmates' intake interviews, Perry found that besides being rounded up in raids, some of the women who went to Lansing in those days had been turned in out of revenge, by their boyfriends, after arguments. Another story kept coming up.

"The women would be going to a dance in this town two hours away," Perry says, "and on the way home, they reported what we would now call date rape. The man drove them out into the middle of nowhere and said, 'Have sex with me or I'll leave you here.'"

Some women turned themselves in because they didn't have money to get treated anywhere else, so they headed to the farm for what was, in the days before penicillin, ineffective (and often toxic) treatment.

"To get treatment for syphilis and gonorrhea was very expensive, and the state did not invest in free public health clinics during this time, so a lot of women didn't have any options," Perry says. "These women were responsible, they were trying to take care of themselves. They just didn't have the resources. It's problematic that they had to turn themselves into a prison to get treatment."

They were usually in for two or three months. And there's little information about what happened to women after they left the farm.

"They didn't do a lot of parole work, so we don't have a great paper trail for what happened to these women," Perry says, noting that most of them were between 16 and 22, the target age for social reformers and police intent on preventing promiscuity.

"In some ways they were still pretty mobile. Not all of them had established families yet, so they may have been able to move on," Perry says, "but other women were older or lived in small towns where maybe everyone knew they were sent to the farm for having this disease, which would have carried a stigma."

"I hate to admit it," Myer says, "but I grew up in Kansas, I was educated here, and I was not familiar with what Chapter 205 even was. I guess we didn’t talk about it in history class."

But her museum's display is helping to make up for that (the images are also viewable online).

As Darby was in the process of digitizing the intriguing images, Myer saved some of them to her phone because she was eager to show people.

"I’d say, 'Look at this picture.' They’d say, 'When’s this from? Fifteen years ago? Twenty years ago? They’re black and white, so maybe the ‘80s?'"

No, Myer would explain. "This was 1920s. People were really surprised."

What makes the images "humbling," she says, is that "these people look just like you and me. Which is the neat thing about photography, especially these high-quality images. It's hard to believe these images were taken so long ago."

Nikki Perry has a similar feeling.

"The pictures are such high quality that it makes you feel like the woman is standing there and you really want to know even more about their stories," she says. "Who were these women? Where did they work? Were they married? Did they have children?"

Besides knowing that thing about their health, there’s really only one thing Myer knows for sure: They were Kansans.

Faces of the Kansas State Penitentiary is online and up through January 2018 (and may be extended later into the spring) at the Lansing Historical Museum, 115 E. Kansas Avenue, Lansing, Kansas, 66043, (913) 250-0203. The museum has extremely limited hours: Fridays 1-5 p.m. and by appointment.

C.J. Janovy is an arts reporter for KCUR 89.3. You can find her on Twitter, @cjjanovy.