Eds. note: We are re-airing this story Jan. 2 as we look back on 2014. Jeff Piehler died in November 2014.

Local woodworker and artist Peter Warren met Dr. Jeff Piehler, a retired thoracic surgeon, at an art opening some years ago. But last year, the doctor came to visit Warren at his studio with an unusual request.

“He came to me and said ‘what do you think about building a casket?’” Warren said. "I told him I was fine with that."

Building his own casket

Piehler is battling Stage 4 metastatic cancer. It has infiltrated his bones, and he knows he’s going to die soon - most of the time he’s at peace with that. But after attending a friend’s funeral where the deceased was lying in an elegant padded casket, Piehler decided he wanted something different.

He’d already committed to being cremated, and he’d planned for his body to be at his funeral, unexposed, to help friends and family say goodbye. But now he knew he wanted to make his own casket and it would be wood.

Working Together

It took Piehler and Warren about four months to complete the coffin, and now it rests in a corner of Warren’s downtown Kansas City shop. It’s a milk chocolate stained rectangular box, rippled with blond waves. This is characteristic of the old growth Southern Yellow Pine that Warren and Piehler used to make the coffin. It has the same look as a chest that might hold your grandmother's blankets.

Inside the woodworking studio, Peter Warren shows me the table where he measured Piehler’s body to determine the dimensions of the casket. He says this was a strange experience.

“'I’m gonna need you to get up on here,'” Warren told Piehler, 'lay down while I trace you.'"

"Very bizarre,” Warren says of the experience.

Dealing with difficult issues

The two men were able to crack jokes through the process. Piehler worried the casket was going to be too heavy, that pallbearers might drop him and he’d fall out.

“Don’t worry,” Warren teased, “that won’t be your problem.”

The conversation shifted to the casket’s interior space. That too, Warren says, was strange.

“How much room do you need?” Warren asked the doctor. “Well, I dunno, just put me in there,” the doctor replied.

Warren said he was uncomfortable with the idea that the doctor was crowded in his casket. He wanted to make sure his nose wasn’t touching the top of the lid. He told Piehler he was going to sew something plain and simple to soften the bottom of the box.

Piehler did much of the sanding of the box himself, and it has a fine sheen.

There were many days, Warren says, they didn’t work at all. They’d sit outside and have a beer, talk about living and dying. They'd laugh and cry.

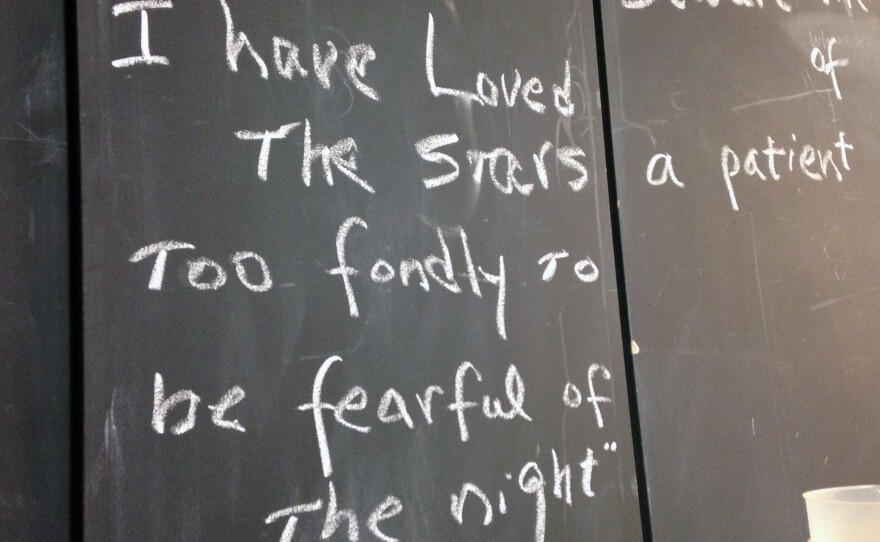

The doctor sometimes scrawled lines from literature and poetry on the woodworker’s white board.

They decided to inscribe one his favorite lines on the inside of the casket’s lid.

“I’ve loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night,” it reads.

Warren takes comfort imagining his dear new friend will be reading that line once he's in the box.